“Necessity may be the mother of invention, but frustration is the father of necessity.”

So says this year’s MassTLC Commonwealth Award recipient, Bill Warner. When he reflects on his long track record of technological innovation, Bill points out that inventors create new solutions because they are frustrated with the state of things and see another way. Inventors also know that no one else is going to fix the situation causing their frustration, they are the ones who must do it. Throughout his life, Bill has tackled frustrations head on and developed better ways of doing things that have had profound impacts on others. From creating a whistle-controlled device that a quadriplegic could use to perform an array of tasks to developing the first digital non-linear editor, he has created a better way to do things many times.

Although he didn’t know the word “engineer” as a child, Bill always had that type of brain. He was into building things, solving problems, and making things work. When he was ten, he was exposed to the world of engineering via what he describes as his “first online engineering class,” also known as the television show, “Star Trek.” The inventions – from speech recognition to hand-held medical devices – fascinated him, but he was also moved by the human element of the show. The story was hopeful and embraced the need to confront and work through problems together. The impact on a ten-year-old boy was, as Bill says, “hard to overestimate.”

His engineer’s spirit is combined with an entrepreneur’s mindset. Bill attributes the latter to his upbringing. His father owned a company that made aluminum extrusions, and his mother was a successful real estate agent who loved public speaking. Dinner conversation centered on business topics and new ideas, never on having a boss or being frustrated at work. Bill always assumed he would have his own company too. That assumption became reality in a surprising way.

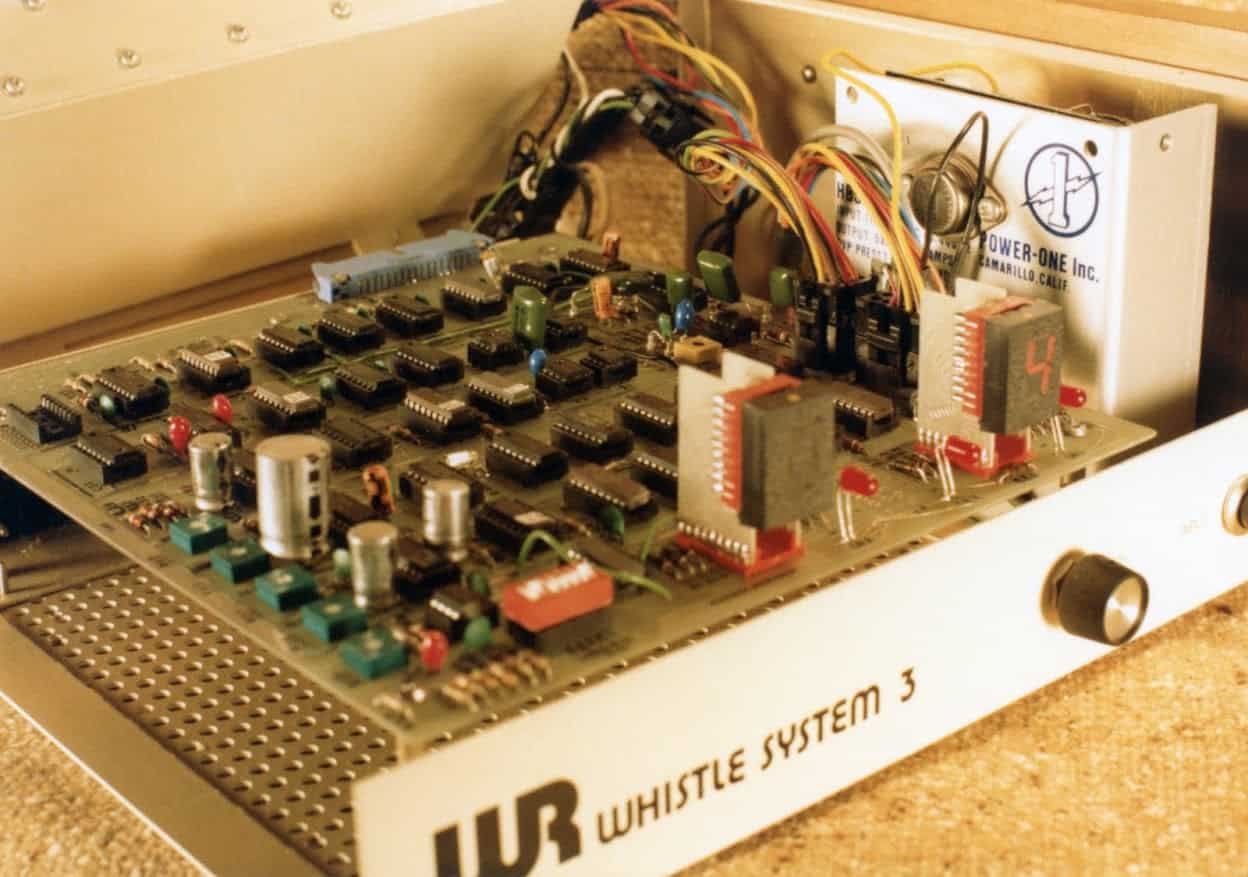

When he was 18, Bill suffered a spinal cord injury that initially left him using a wheelchair, and eventually crutches. While rehabilitating after the accident, Bill shared a room with three other young men who also had sustained serious injuries. One of them, Tom Wade was completely paralyzed and could not even hang up a phone after finishing a conversation. Tapping into his problem-solving mindset, Bill thought that there should be a way for Tom to control things on his own. After some research and a visit to Canal Street in New York City, which at that time was a mecca for surplus mechanical gadgets and parts, Bill took a whistle switch – a device controlled by blowing air through a plastic whistle – and vending machine parts to create a sequencer that could control multiple actions. After some initial problems and with the help of his father’s manufacturing resources, Bill created a working device based on a mechanical sequencer. That was in 1975.

Around that time, his father suggested that Bill meet a man named, John Beall. A self-described “dirt farmer from Louisiana,” John was working on making a digital IBM channel switch using emitter- coupled logic, which was heavyweight technology at that time. When John heard about Bill’s sequencer, he immediately suggested that Bill make it with digital logic integrated circuits rather than mechanical relays. John handed Bill a book on digital logic and sat him down with one of his lab techs to build a device right then and there. Which Bill did. The two teamed up to start Bionic Control Corporation. This connection with John was a turning point for Bill – it opened up a new world of engineering knowledge to him and also helped him create a working product that not only helped people but also bolstered Bill’s eventual application to MIT the following year.

coupled logic, which was heavyweight technology at that time. When John heard about Bill’s sequencer, he immediately suggested that Bill make it with digital logic integrated circuits rather than mechanical relays. John handed Bill a book on digital logic and sat him down with one of his lab techs to build a device right then and there. Which Bill did. The two teamed up to start Bionic Control Corporation. This connection with John was a turning point for Bill – it opened up a new world of engineering knowledge to him and also helped him create a working product that not only helped people but also bolstered Bill’s eventual application to MIT the following year.

While at MIT, Bill continued to work on his whistle system, once again advancing the technology. He went from digital logic to a system controlled by a microprocessor. He also began a lifelong interest in hand-pedaled bikes. His MIT thesis was on improving a hand cycle. This interest led him to start New England Hand Cycles in 1980. He’s now looking into electric cycles, once again advancing with technological progress.

Another time that Bill decided to tackle a frustration that others were unwilling to solve was when he came up with  the idea of a digital, non-linear video editor. At the time, Bill was working at Apollo Computer as a product manager, a job that required him to make demonstration videos for customers and salespeople. The editing process was painful, slow, manual, and decidedly linear. The constraints of having to edit in this fashion finally became too much for Bill, and one day he announced that he would no longer be doing things that way. Once again, he decided to move from the physical approach to a problem to a digital one. He developed a digital, non-linear editing system and went on to found Avid Technology, the leader in the digital non-linear editing field, in 1987. The technology has garnered Emmys and a technical Oscar.

the idea of a digital, non-linear video editor. At the time, Bill was working at Apollo Computer as a product manager, a job that required him to make demonstration videos for customers and salespeople. The editing process was painful, slow, manual, and decidedly linear. The constraints of having to edit in this fashion finally became too much for Bill, and one day he announced that he would no longer be doing things that way. Once again, he decided to move from the physical approach to a problem to a digital one. He developed a digital, non-linear editing system and went on to found Avid Technology, the leader in the digital non-linear editing field, in 1987. The technology has garnered Emmys and a technical Oscar.

These would be achievements enough for most people, but not for Bill. After leaving Avid, he went on to found Wildfire Communications in 1992. Wildfire’s technology was an electronic assistant that worked over the phone, essentially a precursor to Siri, almost twenty years before Siri came into being. The company was acquired by Orange in 2000.

So, what does a serial entrepreneur do after a successful exit? Work on a new product? Support other entrepreneurs? Invest in startups? Why not all three? In 2000, Bill created Mapjunction, to show what Boston looked like historically and what it would look like after the Big Dig was completed. Once again, Bill turned his attention to an intractable problem – how to align historic maps of a dramatically changed city geography and overlay them, compare them, present them. The result, five years before Google Maps, was Mapjunction, which is still in use and free to the public.

Supporting other entrepreneurs has always been important to Bill as he recognized the impact that individuals have had on him and his success throughout his career. With that desire to help in mind, Bill launched the Collaboration Space at Warner Research (now called the Brickyard Collaboration Space) in 2002. Once again, he was ahead of the pack – he created an inexpensive space for entrepreneurs to work and collaborate, well before coworking space were common. He also turned to angel investing and has invested in over 50 companies, including Quickbase and Lightcraft Technology. Bill is an unusual investor in that he is not as focused on making money as he is in helping others and learning about new technologies.

Supporting other entrepreneurs has always been important to Bill as he recognized the impact that individuals have had on him and his success throughout his career. With that desire to help in mind, Bill launched the Collaboration Space at Warner Research (now called the Brickyard Collaboration Space) in 2002. Once again, he was ahead of the pack – he created an inexpensive space for entrepreneurs to work and collaborate, well before coworking space were common. He also turned to angel investing and has invested in over 50 companies, including Quickbase and Lightcraft Technology. Bill is an unusual investor in that he is not as focused on making money as he is in helping others and learning about new technologies.

Bill also mentors and invests in entrepreneurs via TechStars Boston. He was instrumental in bringing Techstars to Boston in 2008 when it expanded from its first home in Boulder, Colorado. His interest in mentorship and the startup community also led him to found the Innovation unConference, a MassTLC event dedicated to helping entrepreneurs find new helpers, whether they are mentors, technical experts, or co-founders.

We are excited to recognize and celebrate Bill for his wide-ranging, enduring, and impactful contributions to the Massachusetts technology community. Join us on November 6th when he will be accepting the Commonwealth Award.