Artificial intelligence (“AI”) is all around us. It allows us to unlock our smartphones with just a glance. It can customise the temperature of our home or recommend television shows based on things we enjoyed watching before. It may soon drive our cars for us. Through the combination of increasing computing power and massive amounts of data, AI has made unprecedented advances in recent years in its ability to make predictions and solve problems. As a result, AI has become a vital part of our everyday lives.

And soon, the medications we take each day may also be identified and developed at least in part by AI. This article examines strategic intellectual property considerations for innovative pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies that are developing AI systems or using third-party systems to enhance drug discovery, clinical trials, manufacturing, or other processes.

AI is Transforming the Life Sciences Industry

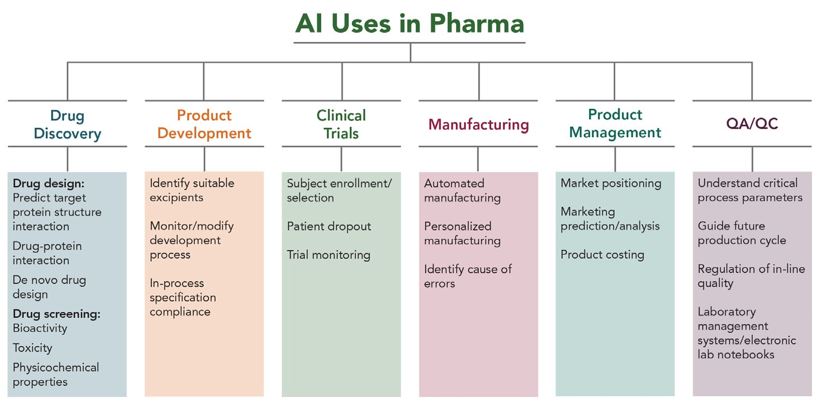

AI and machine learning (“ML”) are revolutionising the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. While drug discovery may be the most well-known use of AI and ML in these fields, the technologies have a wide range of other applications in these industries, as shown in Figure 1 below. AI and ML are also accelerating innovation in developing pharmaceutical formulations, predicting protein structures, designing clinical trials and analysing the data, and speeding up manufacturing and ensuring better quality control.1,2,3

Figure 1: Application of AI in various aspects of the pharmaceutical industry

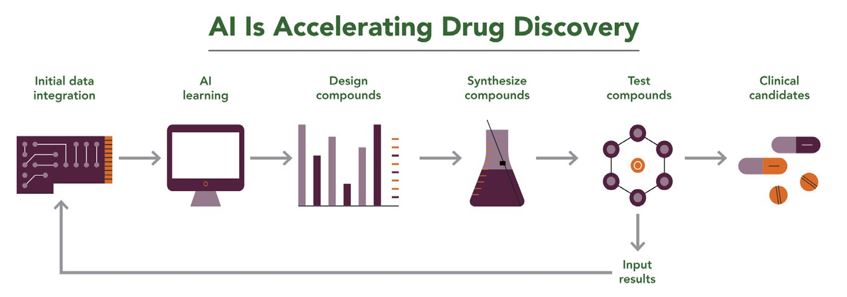

For many life sciences companies, data such as compound libraries may be among their most valuable assets. AI allows companies to leverage those data to more rapidly identify drug targets and advance them through clinical trials. As shown in Figure 2, AI can use those data sets to predict which compounds might have desired chemical or biological properties, drastically reducing the time needed to identify candidates for further laboratory or clinical testing.

Figure 2. A workflow applying AI to accelerate lead compound identification

As just one recent example, the biotechnology company Evotec recently announced a phase 1 clinical trial on an anticancer molecule that was co-invented and developed in partnership with Exscientia, whose AI platform technology computationally analyses the properties of millions of small-molecule candidates to identify a handful suitable for further testing.4,5 Using AI allowed the companies to identify the candidate molecule in just 8 months.

AI thus has the power to reduce the time and costs of drug discovery and increase the number of new therapies available. A recent analysis by Morgan Stanley Research concluded that even modest improvements in early-stage drug development success rates made possible by AI and ML could lead to an additional 50 novel therapies over a 10- year period, reflecting a $50 billion market opportunity.6

It is therefore no surprise that pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies are racing to implement AI and ML to improve their pipeline and reduce costs. Indeed, a recent survey of pharmaceutical and biotechnology professionals indicated that 80% were already using AI technologies in their work or were planning to do so.4 AI is critical to remaining competitive in the pharmaceutical field by reducing the high costs of bringing new drugs to market.

Given the rapid pace at which pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies are developing or adopting AI, companies must have a plan to safeguard their innovations and avoid common intellectual property (“IP”) pitfalls.

Claim Strategies to Satisfy Subject Matter Eligibility Requirements for AI- Related Inventions

One of the most critical issues facing AI and ML inventions is the increasing difficulty of meeting the patent eligibility requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 101, particularly for software- and computer-implemented inventions. The Supreme Court’s decision in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International created a two-part test for determining patent-eligibility, which has led to more patents being invalidated.8 The first step under Alice asks whether the claims are “directed to” a patent-ineligible abstract idea, natural phenomenon, or law of nature. Under the second Alice step, claims that are directed to such a concept are only patent eligible if they contain an “inventive concept” sufficient to transform any underlying abstract idea or law of nature into a patent-eligible application. The prohibition on patenting abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomenon has proven particularly problematic for AI- and ML-based inventions, which are often rejected as being directed to an abstract idea based on their reliance on mathematical formulas or algorithms to accelerate processes that might otherwise be performed by humans.

Alice’s subject matter eligibility framework has made it increasingly difficult to obtain patents covering computer-implemented technology, including AI. And in litigation, patent owners now routinely see motions to dismiss based on Section 101 challenges, which can result in an early ruling of invalidity before the case even gets going.

So, what can companies do to obtain and protect patents covering AI and ML inventions? Recent cases provide some guidance. In CardioNet, LLC v. InfoBionic, Inc., for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed a district court decision dismissing a patent owner’s infringement claims and invalidating the patent under Section 101. The Court concluded that the claims, which recited cardiac monitoring systems, were directed to an improved cardiac monitoring device, not merely the abstract idea of distinguishing between atrial fibrillation and flutter based on the variability of the irregular heartbeat.9 The Court credited statements in the patent’s written description explaining how the invention achieves technological improvement over past monitoring devices and noted that the claims “‘focus on a specific means or method that improves’ cardiac monitoring technology.”10

Similarly, in Visual Memory LLC v. NVIDIA Corp., the Court reversed a district court decision dismissing an infringement suit and invalidating the patent under Section 101.11The claims in Visual Memory were directed to a computer memory system that improved performance by using certain “programmable operational characteristics” to control how data is stored in different types of memory based on the type of processor connected to the system. The Court held at step one of the Alice inquiry that the claims were “directed to an improved computer memory system, not to the abstract idea of categorical data storage.”12As in CardioNet, the Court credited details in the specification regarding how the memory system reflected a technological improvement over prior systems and the advantages made possible by that technological improvement.13

Federal Circuit cases also show common features of patent claims that fail to meet today’s heightened Section 101 standard. Of particular relevance for AI and ML inventions, courts routinely hold claims ineligible that recite collecting, analysing, and reporting data. In Bot M8 LLC v. Sony Corp. of America, for example, the Court upheld summary judgment that a patent was invalid under Section 101.14 The district court concluded that claims directed to increasing or decreasing the difficulty of a video game based on the players’ previous performance was directed to an abstract idea, and that the claims failed to provide any “inventive concept” under Alice step two because they involved only “the conventional computer task of gathering, manipulating, transmitting, and using data.”15 The Federal Circuit affirmed, noting that “neither the patent specification, patent owner, or patent owner’s experts articulate a technological problem solved by” the patent.16

These cases show the importance of drafting claims that reflect a technological improvement over the prior art and do more than manipulate data using conventional computer components. Further, the patent specification must detail how the claimed invention improves the underlying technology and the resulting advantages. Including these statements in the patent is particularly important for surviving a motion to dismiss, which takes place early in the case and is usually decided based solely on the contents of the complaint and the patent itself.

Can an AI System Be an Inventor?

One interesting question regarding AI-derived inventions has been answered recently. During drug discovery, an AI algorithm may be used to derive a new compound with a particular therapeutic effect. But can an AI system be an inventor? In a recent test case, Thaler v. Vidal, the Federal Circuit held that an AI system cannot be an inventor under U.S. law. Dr. Stephen Thaler created an AI system called DABUS, or “device for the autonomous bootstrapping of unified sentience.” Dr. Thaler contends that DABUS created two inventions on its own — an interlocking container system and a controllable light source — without any contributions from him. He filed patent applications on those inventions in several countries designating DABUS as the sole inventor, leading to decisions by patent offices and courts around the world on whether an AI system can “invent” a patent.17

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected two patent applications naming DABUS as the inventor.18 Dr. Thaler challenged those decisions up to the Federal Circuit, which upheld the determination that an “inventor” under the Patent Act must be a human.19,20The Court reasoned that the patent statute requires that an inventor be an “individual,” which refers to a natural person and not a computer system.21

Most other countries have reached the same conclusion. The European Patent Office (EPO), for example, rejected an application naming DABUS as the inventor, and the EPO Board of Appeals confirmed that a named inventor must be a human for the EPO to grant a patent.22 The United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office rejected corresponding applications for similar reasons. The UK Supreme Court of the United Kingdom plans to consider the case on appeal.23 In Australia, a federal court initially held that DABUS could be listed as an inventor,24 but a higher court reversed the decision, bringing Australia back in line with the United States and Europe.25So far, only one country determined that an AI system can be an inventor. In July 2021, the South African Companies and Intellectual Property Commission accepted Dr. Thaler’s application and granted the first patent in the world naming AI as the inventor.26

While the United States and most other countries have concluded that patents may only list human inventors, there are still some strategic considerations companies should keep in mind. The written description requirement of Section 112 requires a patent specification to include sufficient detail to show that the inventors had possession of the full scope of the claimed invention. The amount of detail required will vary depending on the role AI played in the invention and, depending on the invention claimed, companies should consider whether the creators of the AI system should be listed as inventors. A patent specification must also contain sufficient detail to enable a person of ordinary skill in the relevant art to practice the claimed invention without undue experimentation. It could pose enablement problems if the listed inventors of an AI-derived invention cannot describe how to make the claimed invention because it arose from the operation of a machine-learning process that the inventors may not be able to recreate.

Trade Secrets Are an Important Part of Protecting AI Inventions

Patents are a vital piece of protecting AI innovations, particularly for innovator pharmaceutical companies seeking to protect new chemical entities and associated methods of treatment. The right to exclude others from making, using, selling, and importing the claimed invention allows patent owners to erect a significant barrier to market entry that can deter competition and protect the patent owner’s freedom to operate.

Yet, for innovations that rely heavily on data and know-how, for which it can be challenging to obtain patents, trade secret protection is an important aspect of IP protection. For example, certain aspects of new model-training methodologies, optimising model parameters, negative know-how (i.e., what not to do), and many other data-driven aspects of AI systems may face an uphill climb given current patent eligibility requirements. For such innovations, even if you obtain a patent, it can also be difficult to establish infringement by a competitor who you suspect is using your technology. For those kinds of innovations, trade secrets can provide robust IP protection if proper steps are taken to ensure confidentiality.

Trade secrets can protect any information that derives independent economic value from not being generally known or ascertainable through proper means. That could include data about protein structure, customer lists, machine learning algorithms, source code, chemical process parameters such as reaction temperature or pressure, and nearly any other kind of information. And unlike a patent, which provides a limited period of protection (generally, 20 years from the date of filing), a trade secret can endure for as long as the information remains secret and continues to have value.

Trade secrets do have certain disadvantages. For example, trade secrets do not protect you if a competitor independently develops the same information or technology. A competitor could even file a patent application seeking to protect something your company had held as a trade secret. Nor does a trade secret protect against reverse engineering. And, once the information is no longer secret, the trade secret right is extinguished.

Companies that have valuable data should ensure they have adequate procedures to protect their secrecy. That includes identifying and labelling trade secrets, limiting access to the smallest number of people who need to see the information, conducting trainings to ensure employees understand their obligations to safeguard confidential information, requiring nondisclosure agreements and restrictive licenses with third parties, maintaining cybersecurity policies, and enacting robust onboarding and off-boarding procedures.

Pharmaceutical companies should consider a hybrid approach for protecting AI-related innovations. For example, proprietary raw and training data, optimised model parameters, implementation know-how for training and utilising models, and other confidential information covering aspects of AI that are difficult to reverse engineer may be particularly well-suited for trade secret protection. Meanwhile, other aspects of the technology, such as the AI system or a drug developed using an AI system, can be protected by patents. Companies should also carefully consider what information their scientists publish until they have decided whether to keep that information as a trade secret or to seek patent protection.

AI Partnerships and IP Ownership

Because life sciences companies may lack expertise in software and computer system development, many engage in research agreements or partnerships with other industry partners. These collaborations often raise IP issues, such as inventorship and ownership of any IP generated through the project, rights to preexisting IP, and the parties’ rights upon termination of the collaboration.

Companies should evaluate these IP issues as early as possible, ideally before the project starts, to avoid any potential issues from frustrating business goals. For example, contracts that define IP ownership and the ownership rights of the data, AI system, AI implementation know-how, and AI-created inventions in relation to the collaboration can help reduce disputes and foster partnership. Nondisclosure agreements are also a critical aspect or any joint venture, especially if trade secret protection is contemplated.

Conclusion

AI and ML have enormous potential to accelerate drug discovery and decrease costs, allowing innovator pharmaceutical companies to bring more new therapies to market. As life science companies boost investment in AI, carefully considering IP strategy can give them a competitive edge by protecting their innovations and giving them freedom to operate.

___

This post was originally published by Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP.

For Endnotes, please visit the original post.