James Bessen, Executive Director, Technology & Policy Research Initiative, Boston University, will lead a discussion at TRANSFORM on the challenge of ensuring that workers have the requisite tech skills in a rapidly changing economic and technologic landscape. For an advanced look at some of the topics that he will be addressing, read his article on automation and its impact on the labor market.

Automation isn’t just for blue-collar workers anymore. Computers are now taking over tasks performed by professional workers, raising fears of massive unemployment. Some people, such as the MIT professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, identify automation as a cause of the slow recovery from the Great Recession and the “hollowing out of the middle class.” Others see white-collar automation as causing a level of persistent technological unemployment that demands policies that would redistribute wealth. Robot panic is in full swing.

But these fears are misplaced—what’s happening with automation is not so simple or obvious. It turns out that workers will have greater employment opportunities if their occupation undergoes some degree of computer automation. As long as they can learn to use the new tools, automation will be their friend.

Take the legal industry as an example. Computers are taking over some of the work of lawyers and paralegals, and they’re doing a better job of it. For over a decade, computers have been used to sort through corporate documents to find those that are relevant to lawsuits. This process—called “discovery” in the profession—can run up millions of dollars in legal bills, but electronic methods can erase the vast majority of those costs. Moreover, the computers are often more accurate than humans: In one study, software correctly found 95 percent of the relevant documents, while humans identified only 51 percent

But, perhaps surprisingly, electronic discovery software has not thrown paralegals and lawyers into unemployment lines. In fact, employment for paralegals and lawyers has grown robustly. While electronic discovery software has become a billion-dollar business since the late 1990s, jobs for paralegals and legal-support workers actually grew faster than the labor force as a whole, adding over 50,000 jobs since 2000, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The number of lawyers increased by a quarter of a million.

Something similar happened when ATMs automated the tasks of bank tellers and when barcode scanners automated the work of cashiers: Rather than contributing to unemployment, the number of workers in these occupations grew.

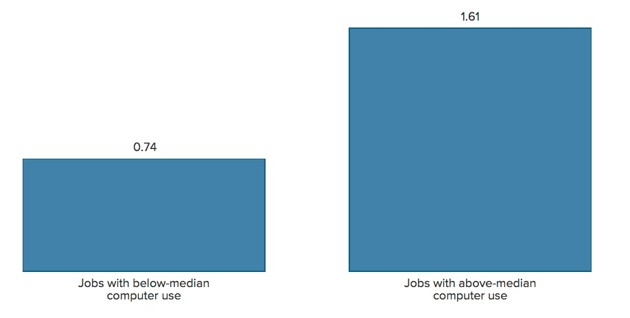

These are not special exceptions. On average, since 1980, occupations with above-average computer use have grown substantially faster (0.9 percent per year), as shown in this chart:

The Average Annual Percentage Growth in Jobs Between 1980 and 2013

How can this be? It might seem a sure thing that automating a task would reduce employment in an occupation. But that logic ignores some basic economics: Automation reduces the cost of a product or service, and lower prices tend to attract more customers. Software made it cheaper and faster to trawl through legal documents, so law firms searched more documents and judges allowed more and more-expansive discovery requests. Likewise, ATMs made it cheaper to operate bank branches, so banks dramatically increased their number of offices. So when demand increases enough in response to lower prices, employment goes up with automation, not down. And this is what has been happening with computer automation overall during the last three decades. It’s also what happened during the Industrial Revolution when automation in textiles, steel-making, and a whole range of other industries led to a major increase in manufacturing jobs.

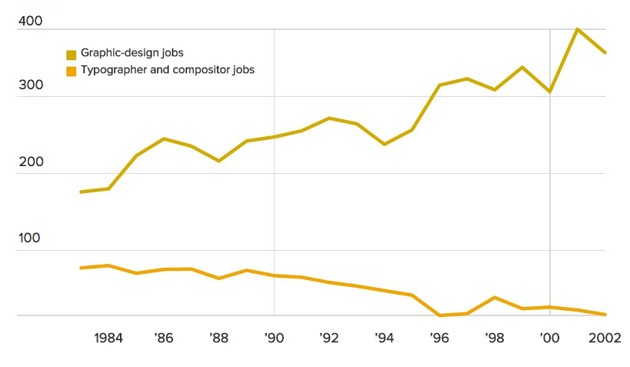

But not all of the news about computer automation is good. Some of that growth in computer-using occupations has come at the expense of other occupations. As depicted in the chart below, desktop publishing systems have meant fewer jobs for typographers, as graphic designers took over their work. Computerized phone lines meant fewer jobs for telephone operators, but more jobs for receptionists. These aren’t examples of computers “stealing” jobs; they are cases where computers helped some workers take work from others. Workers with computers frequently substitute for workers in non-computerized jobs.

Number of Graphic-Design Jobs vs. Typographer Jobs, in Hundreds of Thousands

So, while computers create jobs in some occupations, they also reduce employment in others. The total effect on unemployment depends on which tendency is stronger. Some of my research shows that the net effect, across the economy, is a wash: Computers create about as many jobs as they eliminate. In other words, automation is not causing persistent unemployment.

That could change decades into the future, as new generations of software powered by artificial intelligence becomes ever more capable of advanced tasks. But in the near term, the story is much different. A new study by McKinsey & Company took a detailed look at work tasks that are likely to be automated and found that only about 5 percent of jobs are at risk of being completely automated in the near future. The main effect of automation for the time being will not be to eliminate jobs, but to redefine them—changing the tasks and the skills needed to perform them.

Even so, this means that automation poses a major challenge. There will be jobs, but workers will only be able to get them if they have the new sets of skills that computers make important. It’s not just computer skills that are in demand, because automation can change the nature of jobs. For example, bank tellers have become more like marketing specialists, telling customers about bank loans, CDs, and other financial offerings.

Learning new skills is a significant social challenge as well. My research suggests that the jobs that get transferred to other occupations tend to be predominantly low-pay, low-skill jobs, so the burdens of automation fall most heavily on those least able and least equipped to deal with it. And often the new skills need to be learned on the job, so experience matters. To meet this challenge, some community colleges are collaborating with local employers to create work-study programs that allow trainees to learn on the job as well as in the classroom. Some trade groups are promoting skill-certification programs, which allow employers to recognize skills acquired through experience. These are the kinds of policies that can help overcome the real burden of automation. They deserve more attention than any panic about a supposed robot apocalypse.